Perhaps the most predictable response that we receive when speaking out against book bans is that nobody is actually banning books. Proponents of bans shift the narrative, saying that a book is only banned if it is completely unavailable, no longer published and all copies removed from any means of access. According to this logic, if you can still purchase a book at Barnes & Noble or borrow it from the public library, it’s not banned. It is pretty apparent that book banners strongly dislike the label. I suspect there are several reasons for this.

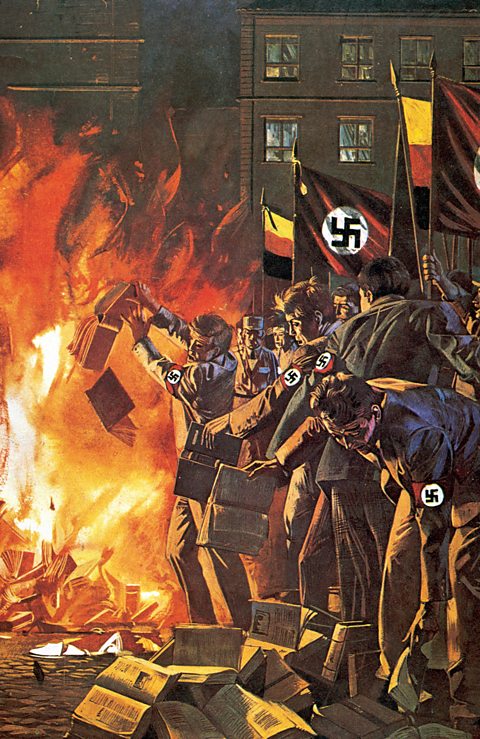

First, there’s truth to saying that book banners are never on the right side of history. From slave owners to Nazis, history teaches us that those that suppress ideas and voices are never the good guys.

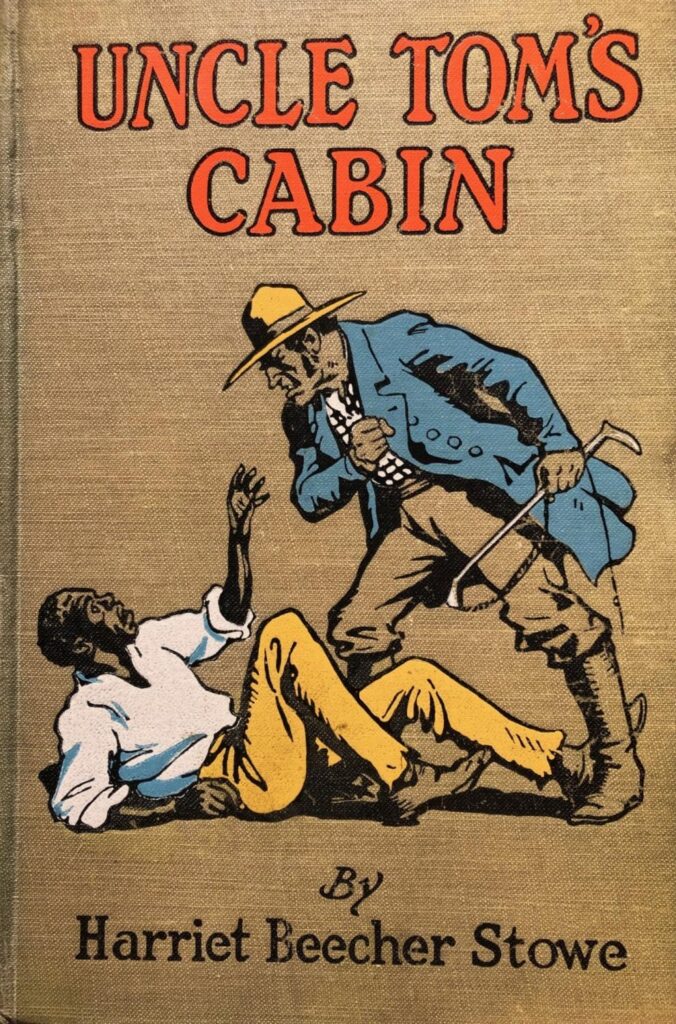

Before the Civil War, books that described the horrors of slavery were regularly censored. Slave owners commonly banned the abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and withheld access to the Bible to prevent enslaved people from reading the story of the Exodus, where Moses led slaves to freedom.

The Nazis created a blacklist of books to be burned, targeting any content that they believed would threaten their total control, especially works with Jewish cultural influences. Books by Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Helen Keller, Ernest Hemingway and Jack London were burned in a series of massive bonfires that destroyed thousands of books.

It probably doesn’t feel good to be associated with Nazis and slaveholders, which is why the modern-era banners work diligently to change the narrative and insist they aren’t banning books. For individuals who claim to be patriotic, apple-pie loving Americans, aligning with Nazis doesn’t really fit the image.

Second, book banners are aware that book bans are unpopular and can have political repercussions. Last year’s school board elections in Iowa exemplify this, as twelve out of thirteen people running on a book banning platform with a Moms for Liberty endorsement were defeated by anti-ban candidates.

This isn’t just an abstract statement: Michelle Veach, a candidate in Johnston infamous for her attempt to ban books and her use of the n-word at a school board meeting; Teri Patrick, a candidate in West Des Moines who attempted to have the sheriff arrest school librarians for keeping “Gender Queer” in the library; and Patty Alexander, a candidate in Indianola who tried to have the district adopt Moms For Liberty’s Book Looks rating system to remove books deemed “pornographic” by unqualified individuals, were all trounced in the election. People don’t like book bans, so book banners lie to convince people they’re not actually banning books.

Book banners often argue over the semantics of the term “ban” to distract from their actual actions.. If we get bogged down in debates about whether removing books from school constitutes a ban, we lose focus on the dire consequences of these actions. I’m not interested in playing their games and debating definitions. Instead, we should focus on why removing books from school libraries due to objections over content is unconstitutional and harmful to kids.

Why is the removal of books from schools a ban?

A ban, in simple terms, is to legally or officially prohibit something. In the context of school book bans, this means that books are removed from the school library or classroom because someone—a parent, school board member, or lawmaker—objected to their content.

Understanding the basics of book banning is pretty easy: It used to be in a public school and now it is not because someone didn’t like what was in it. Once a book is included in a public school library, students have a First Amendment right to access it. If a book is removed because someone dislikes its ideas or for partisan, political, or viewpoint-based reasons, this removal (aka a ban) violates the First Amendment rights of the students in that school.

Libraries, including school libraries, are places where people can access a wide range of viewpoints, content, genres and experiences. When the government—whether federal, state, or local entities like school boards—uses its power to restrict access to certain viewpoints or content, it engages in unconstitutional censorship. Often, these campaigns to remove books from schools target books that touch on themes of racial inequity, mental health, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

Does it matter if people can still get the books at the bookstore or the public library?

Book banners always immediately default to the argument that it’s not a ban if you can get the book from the bookstore or a public library. This is merely a deflection and, for several reasons, is irrelevant to whether a book that’s removed from the school is banned.

First, let’s consider the extreme privilege of telling parents to simply buy a book for their kid or make a trip to the public library and hope that it’s available. There’s no guarantee that a student or their parents have the resources to purchase a book, access to a library nearby, a library card (only 51% of adults have one), transportation to get to the library, or even know what books might interest them. Telling parents to get the book elsewhere doesn’t address the problems around the removal of books from schools. Setting aside the First Amendment issues, it also includes the logistical challenges of eliminating easy access to free books and the invaluable resource of a school librarian.

Next, it’s difficult to reconcile the logic of directing parents to take their children to bookstores or public libraries with the reasons behind removing books from schools in the first place. In Iowa, proponents of SF496 claim the law aims to protect children from exposure to pornography or obscenity in schools. According to this law, any book containing a depiction or description of a sex act is pornographic and must be removed. As a result, school districts have banned a wide variety of books, including well-known classics like Slaughterhouse Five, As I Lay Dying and Brave New World, award-winning contemporary books by authors like Toni Morrison, John Green, Jodi Picoult and Maya Angelou, non-fiction books, books that appear on AP tests, and books written to help students avoid being victimized by sexual assault.

If these books are pornographic, as our lawmakers claim, it seems strange to suggest that kids can simply get them at a bookstore or public library. If a book is deemed pornographic at school, wouldn’t it also be considered pornographic at the public library?

These two positions are impossible to reconcile: claiming a book is pornographic and should be banned from schools yet suggesting that it’s ok for it to be available to kids at the public library or the bookstore. Providing a child with pornographic material is illegal everywhere: in school libraries, bookstores, and public libraries. Book banners seem to believe that books have chameleon-like properties—pornographic in schools but not in bookstores. This argument is irrational and highlights its inherent flaws.

On top of all that, book banners are now attempting to prohibit book stores from selling these books and are pushing to ban them from public libraries. It’s becoming increasingly clear that this isn’t really about schools–the banners want to erase these viewpoints from existence.

The Supreme Court doesn’t care about whether books are available elsewhere, so why should you?

The Supreme Court has definitively ruled that the government cannot justify violating someone’s First Amendment rights by pointing to other places where those rights can still be exercised.

In Southeastern Promotions, Lt. v. Conrad (1975), the Supreme Court considered a dispute between a theater promoter and a city board overseeing a city auditorium. The promoter sought to lease the auditorium for several performances of the musical Hair. The city board rejected the request, claiming it was not in the community’s best interests. One board member remarked that the theater should only host productions that were “clean and healthful and culturally uplifting.” Although other privately-owned theaters were available for the production, the Supreme Court ruled that the board’s decision was unacceptable. The Court held that violating free speech rights cannot be justified by arguing that those rights can be exercised at a different location or time.

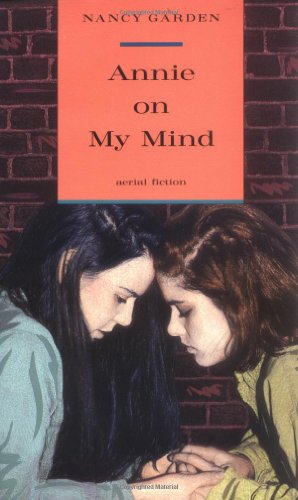

Since then, several courts have applied this principle to cases involving book bans in schools. My favorite case is Case v. Unified School District No. 233, a 1995 lawsuit in Kansas. The public school board removed “Annie on My Mind,” a book that had been in the district’s libraries since the mid-1980s. Those demanding removal even went so far as to burn the book on the steps of the school board office. “Annie on My Mind” is a fictional work about a romantic relationship between two teenage girls and the school board removed it because its members personally disapproved of its content. The defendants argued that students still had access to the book from other sources outside of school. The court rejected this argument outright, stating that “restraint on expression may not generally be justified by the fact that there may be other times, places or circumstances available for such expression.”

Here in Iowa, the federal court judge presiding over the SF496 lawsuit also addressed whether the availability of books from other sources could justify the unconstitutional removal of books from public school libraries. As expected, the judge determined that this does not excuse the infringement of students’ constitutional rights.

This makes sense as a general principle. If the government could justify infringing on people’s First Amendment rights by simply stating that they can exercise those rights elsewhere, the protections afforded by the First Amendment would be effectively nullified. Imagine an upside-down world where the Supreme Court determined that the Des Moines Public Schools were justified in stopping Mary Beth Tinker from wearing her black armband to school because she could have worn it at the grocery store or the movie theater.

Does banning books really affect anyone?

When the government bans books from schools, it signals to students that certain perspectives and viewpoints are unacceptable. It’s no coincidence that the most frequently banned books are written by or depict LGBTQ individuals or people of color. Removing books about race, LGBTQ issues, immigrants, mental health, drug abuse and sexual violence sends a strong message that the advocates of these bans don’t want those stories to be told, implying that certain experiences should be erased. Book bans result in the government determining which viewpoints and experiences are permissible, limiting kids to a narrow set of ideas.

Diverse books can provide an accurate and honest portrayal of the modern teenage experience. The issues affecting teens today—sexuality, mental health, drugs, racism, violence, guns, sexual assault—differ significantly from those faced by previous generations. Kids need access to stories that reflect their own experiences and allow them to learn about the lived experiences of others. Removing diverse stories from our libraries sends the message that those experiences are not valid.

Removing a book here or there under the guise of protecting children might seem to be harmless. However, modern-day book bans are often driven by individuals affiliated with groups tied to dark money, such as Moms for Liberty and No Left Turn in Education. The result is a biased and bigoted reshaping of our school libraries. Behind the façade of concerned parents lies an agenda to reverse progress and perpetuate a worldview steeped in Christian nationalism. As diverse books are stripped from schools, the remaining information available to kids is skewed towards a decidedly ultra-conservative perspective. It appears the far right is using public schools to systemically mold today’s youth to their moral image.

Want to learn more? Check out these great resources:

https://uniteagainstbookbans.org

https://ncac.org/project/the-kids-right-to-read-project/kids-right-to-read